By Frank Chiarenza

(Reprint from Glass Collector’s Digest December/January 1993)

The reverse is also encountered, but less often; that is, pieces made originally in glass and later replicated in other materials. One such item in glass is the subject of this article: namely, a dish in the form of cupped hands with a cluster of grapes and leaves at the wrist, sometimes called “Queen Victoria’s Hands.” Because the design was patented, we are able to state with certainty not only who invented it and when, but also that it was specifically intended to be made in glass. Copies of the same design abound in ceramic and metal, and in various sizes, but all are essentially replicas of the glass original.

For a long time, it was generally thought that the double hands dish was an original creation of the Atterbury Company.2 Only as recently as 1960 did the patent papers come to light when Albert Christian Revi published his discovery, revealing the name of the designer as well as the company specifically assigned to produce it.3We know now that on August 31, 1875, a U.S. Patent (design no. 8585) was issued to George E. Hatch of East Cambridge, Mass., for a “Glass Fruit-Dish,” designating Hatch as the “assignor to New England Glass Company, of same place.” The patent papers include an illustration of the piece, together with a long, detailed description in which Hatch allows for some minor variation in the design, as follows:

“At the base or wrist…I arrange a series or cluster of leaves, the middle one of which extends over and covers the junction of the palms, base of the cluster of acorns or grapes; but the cluster of leaves and grapes may be dispensed with, and some other figure or design substituted in place thereof, without departing from the spirit of my invention… What I claim as my invention [emphasis added] is-The design for a glass fruit-dish, arranged and combined as shown, and having any suitable wrist ornamentation, as described.”4

Before going further, we should address an unresolved question concerning Hatch’s claim that he invented this design. A cupped hands dish, with grapes and leaves, made in graniteware is shown in Richard C. Barret’s book, Benrdngton Pottery and Porcelain (1958), plate 414, and dated circa 1850-1858, much earlier than the Hatch patent date. The similarity between the graniteware (a type of ironstone) and the glass cupped hands is striking—too close, indeed, to be independently conceived or purely accidental. Either Barret errs in dating the graniteware hands (said to be “extremely rare”) or Hatch was untruthful in claiming the design as his own invention. On the basis of Barret’s dating, Arthur G. Peterson believed that Hatch’s design “apparently” was a copy of the Bennington hands.5 Little is known about Hatch, except that he received other patents: one on Dec. 7, 1875, for a novel glass inkwell in the shape of a pear with leaves, and another on Feb. 1, 1876, for a beautiful card receiver formed as a bird with “wings, head, and tail raised, as in the act of commencing to fly.”6 Both of these articles are marked with the patent date as well as Hatch’s own name, and are made of high quality satin-textured milk glass characteristic of New England Glass Company products. Until there is more certain evidence to question Hatch’s veracity and that of the two witnesses whose names appear on the patent papers, we have to regard other cupped hands articles designed as Hatch describes them, whether in glass or in any other material, as products made after 1875.

Only six months after Hatch received his patent, the same design was issued an English Registry mark and number through what appears to have been licensure agreement between an English firm and officials of New England Glass Company (hereafter, NEGC). According to documents preserved in the Public Records Office of the Victoria and Albert Museum, an English Registry for the design was granted on Feb. 23, 1876, to William Ford, “trading under the name of John Ford,” the Holyrood Glass Works, Edinburgh.7 The cupped hands made by Holyrood have frequently been mentioned and pictured in books dealing with English glass.8

Trying to discover the connection between Holyrood and NEGC, I wrote to the Huntiey House Museum in Edinburgh where records of Holyrood Glass Works are preserved. In his reply, Mr. Gordon McFarlan, Assistant Keeper of Applied Art, expressed his puzzlement, too, that the Scottish company “should have issued an article first made in America.” He added that he could find no documents to show any written legal agreement between the two companies for production of the cupped hands dish in England. Nonetheless, he offered a compelling account of why a “link” between theAmerican and the Scottish companies should have existed:

Trying to discover the connection between Holyrood and NEGC, I wrote to the Huntiey House Museum in Edinburgh where records of Holyrood Glass Works are preserved. In his reply, Mr. Gordon McFarlan, Assistant Keeper of Applied Art, expressed his puzzlement, too, that the Scottish company “should have issued an article first made in America.” He added that he could find no documents to show any written legal agreement between the two companies for production of the cupped hands dish in England. Nonetheless, he offered a compelling account of why a “link” between theAmerican and the Scottish companies should have existed:Photo 1—Bronze Hands

“In 1826, Thomas Leighton, foreman of the Holyrood Glass Works, was contacted by Joseph Wing, agent of the New England Glass Company, and recruited for the American company. In order to break his contract he sailed to France, ostensibly on afishing trip; but once across the channel, he shipped to America where he took up his duties as ‘gaffer’ in the New England Glass Company. Despite the circumstances of his departure, Leighton maintained friendly relations with John Ford and we have here a series of letters from Leighton dating from 1828 until 1849, the year of Leighton’s death.”9 Clearly, the connection between NEGC and Holyrood was one of long standing and continued with Leighton’s heirs after his death.

Indeed, when we come shortly to compare the hands dishes produced by both companies, it will be seen that they are virtually identical, except for the markings on the undersides. So alike are they, in fact, that it appears the Holyrood issue could well have been pressed from the very mould created by NEGC whose facilities for making moulds was acclaimed as one of the finest of its day.

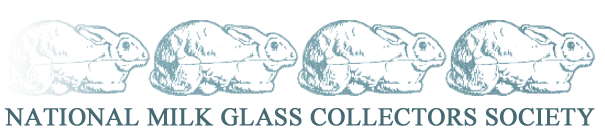

Early in my research, I was able to acquire a Holyrood specimen in opaque white with satin-textured finish; it carries the English Registry diamond mark and number, as well as the U.S. Patent date. By chance, I also found the identical piece made in bronze, carrying the same markings on the underside. The fact that the bronze hands dish is marked with the “Class III” designation in the diamond confirms, of course, that it was originally authorized as an “Ornamental Design in Glass.” Because photographs of metal objects often produce greater clarity of detail than those of glass, the bronze hands shown in Photo 1 reveal very well the features of the Holyrood glass ones.

Early in my research, I was able to acquire a Holyrood specimen in opaque white with satin-textured finish; it carries the English Registry diamond mark and number, as well as the U.S. Patent date. By chance, I also found the identical piece made in bronze, carrying the same markings on the underside. The fact that the bronze hands dish is marked with the “Class III” designation in the diamond confirms, of course, that it was originally authorized as an “Ornamental Design in Glass.” Because photographs of metal objects often produce greater clarity of detail than those of glass, the bronze hands shown in Photo 1 reveal very well the features of the Holyrood glass ones.

My search for an example of the original hands that could definitely be ascribed to NEGC, however, proved difficult. In my collection I already had several unmarked hands of indeterminate age whose features are very similar to the Holyrood issue and, therefore, could possibly be NEGC products. What was lacking to confirm my hunch is a patent date on the undersides. For help, I wrote to Jane Shadel Spillman, Curator of American Glass at the Corning Museum. Her gracious letter in reply stated that although she was well aware of the Hatch patent and the assignment of it to NEGC, she did not know for certain whether NEGC actually produced the hands dish. If they were produced, she thought they may not have been marked in any way with patent or trademark. The Corning Museum does not have an example of it, nor did she know of one in any private collection.10 This information encouraged me to think that perhaps my unmarked examples, so similar to the marked Holyrood dish, might well be NEGC. My major reservations came from the less than optimal quality of the glass, and from their being fairly available.

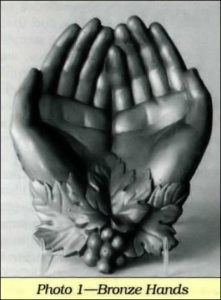

It was only after I had given a “work-in-progress” talk on the hands dish, at the National Milk Glass Collectors Society convention in Arlington, Texas, and nearing the completion of my research, that I happened upon a hands dish (at a show in Massachusetts) that I could definitely assign to NEGC, for the simple reason that it is marked with Hatch’s patent date. The rubbing in Photo 2 shows the date pressed inside the ring-support on the underside, unlike the English dish which carries the U.S. Patent date along the edge, under the cluster of leaves at the wrist (see Photo 3).11

And now, if you compare the NEGC hands dish in Photo 4 (left) with the Holyrood issue (shown right), I think you will see they are identical in every respet, including the same satin finish of the glass. They differ only in the supporting-element on the undersides, a difference simply in manufacturing methods. See Photo 5, showing NEGC (left), Holyrood (right).

Both the NEGC and the Holyrood hands may have been made in small quantities or for only a short period, as neither is at all easy to find. We are left with a question, however, concerning the unmarked examples which, as I have said, are so like the marked one as to suggest either the NEGC mould came into other hands or new moulds, with patent date removed, were cast as replicas of the original. Photo 6 shows two examples, in amber and opaque white, of those I assumed earlier might have been unmarked NEGC products. The maker of these unmarked hands is unknown to me, but they do share features unmistakably like those of both NEGC and Holyrood. In particular, I call attention to the following characteristics which all of them share in common: (1) they measure approximately 71/2″ in length and 53/4″ across; (2) the soft and delicate creases of the palms and fingers are patterned exactly alike;

(3) the nails of both thumbs are well-defined, and the thumbs themselves extend outward slightly from the index fingers at the tips; (4) one grape, at the lower right of the cluster (what might be called the 4 o’clock position) is a bit flatter and slightly depressed below the level of all the other grapes. For some strange reason, the ‘depressed grape’ feature, in Glass Collector’s Digest particular, appears in all other hands I have found (whether old or new, large or small, in glass or other materials) with one notable exception.

That exception is Atterbury’s distinctive version of the hands produced a year or so after the Hatch patent had expired. The term of design patents, as frequently noted, was generally three and a half years, so when the Atterbury Company advertised its “Dual Hand Card Receiver” in its 1881 trade catalog, the company was not subject to a claim of patent infringement. Famed for its own many original patent designs which it guarded with vigilance, Atterbury nonetheless copied the Hatch design, producing a dish of about the same size but with notable difference in mould detail. Photo 7 allows a good comparison of the Atterbury dish (right) alongside the NEGC product (left). If you have Belknap’s book (Milk Glass, 1950) at hand, you will see an excellent full-page photograph of the Atterbury hands (plate 194) to make an even better comparison. Recall the main features of the NEGC/Holyrood hands, and compare them now with Atterbury’s which exhibit the following characteristics: (1) the creases in the palms are not only positioned differently, they are so sharp and deeply impressed as to make it almost appear that each finger has four joints instead of three; (2) thumbnails are present, but the thumbs themselves lap much more over the index fingers and are close-in at the tips, rather than turning out slightly; (3) the grape in the 4 o’clock position is just as fully round, plump, and prominent as all the others.

There are other differences, not easily seen without hands-on (sorry about that!) examination, but when you encounter the Atterbury version, the features listed above will distinguish it from the others. As always, of course, the characteristics of the glass itself and evidence of age should not be overlooked.

Thus, three companies—two American and one English—are known to have produced the cupped hands dish in the late 19th century. As for the unmarked examples, alluded to earlier and shown in Photo 6, they remain a mystery. I believe the opaque pink hands dish shown in Ferson’s Yesterday’s Milk Glass Today (1981), plate 172, and now in my possession, belongs to this unidentified group and is not an Atterbury product. Although the color pink is one of those mentioned in the Atterbury catalog, you will see in the Person photograph that it does not conform to the Atterbury features mentioned above; in particular, the 4 o’clock grape is small and depressed. Other collectors have shared with me their examples of the unidentified hands, in a wide array of colors—from clear frosted to opaque butterscotch— and I tend to think they may be products of a later period. Early in this century, before modern reproductions began to appear, the hands dish was a scarce and expensive collectible, leading one to think these relatively available unmarked ones may not be very old. It is also possible that they may be of foreign manufacture.12

When a new wave of interest in milk glass began to sweep the country in the 1940s, it is not surprising that among the first of the older pieces to be reproduced was the cupped hands dish. Also not surprising, it was Westmoreland Glass Company, acknowledged leader in the milk glass revival, who introduced its version of the hands with great fanfare. Its entry into the glass market was announced in a postal card advertisement for a show in Dallas, Texas (see Photo 8). Together with a Hand vase, it is touted as “sensational” and “never before made in AMERICAN GLASS.”13 From evidence too convoluted to go into here, concerning the agent R.A. Keel named in the postal card, we can date the introduction of Westmoreland’s hands dish round about 1940.14

Early issues of Westmoreland’s reproductions lack the familiar WG logo, which did not come to be used until 1949.15 In a small brochure (undated) Westmoreland shows the hands with the following caption:

“The #51 Hands originally designed for calling cards; it serves also as a single Flower float and as a mint or nut tray. The Hands are said to be from a cast of Queen Victoria.”16

I think we may dismiss as merchandising puffery the oft-repeated nonsense connecting Hatch’s design to England’s queen, but the reference to the dish as “originally designed for calling cards,” tells us that Westmoreland assumed, like everyone else at the time, that the design originated with the Atterbury Company. As a matter of fact, the Westmoreland hands show none of the features of Atterbury; instead, they are faithful copies of the NEGC/Holyrood issues. The postal card boast (“never before made in AMERICAN GLASS”) certainly applies to the Hand vase (from a PV France original), but applies also to the hands dish, if Westmoreland used a Holyrood example, with its English registry marks, from which to cast its mould. In any case, the main features of Westmoreland’s hands replicate those of NEGC/Holyrood—identical pattern of creases in the palms; thumbs slightly extending out at the tips; and, especially, the depressed grape. Photo 9 shows these differences between Westmoreland’s hands, with its popular Roses & Bows decoration (left) and Atterbury’s version (shown right). A slight variation exists in Westmoreland’s early issues, those without its logo, in which we see fairly well-defined thumbnails. The later marked ones do not show this feature, or only faintly. This is easily explained, since Westmoreland made multiple moulds for many of its items both to speed production and to replace worn ones. I have discovered, after months of tracking “leads,” that at least three of the Westmoreland moulds survive to the present day. One is the property of Plum Glass Company in Pittsburgh; two others were purchased upon Westmoreland’s closing by Jeanette Shade and Novelty Company of Jeanette, Pa., later sold to Peltier Glass Company in Ottawa, 111., and from there they went to Gary Levi, Intaglio Designs (formerly Levay Glass Works), Alton, 111. Except for Plum Glass, which began producing the Westmoreland hands (with logo removed) in milk glass and cobalt in 1991, I have no evidence of the other moulds having been put to use by any other glassmaker to date.17

Finally, two other versions should be mentioned to complete this chronicle. The one shown in Photo 10 (left) is most curious, as it has some features in common with the original (the depressed grape, for example), but the creases in the palm are very faint and the notched leaf that rises to cover the junction of the hands bears no resemblance to the others. The workmanship and quality of the glass in this example are poor by any standard. The version shown at the right in this photo is a well-known product of the Avon Company. It was made in Mexico and introduced into the Avon line of products in 1969 as ‘Touch of Beauty Soap Dish.” It differs in size and in the ornamentation at the wrist which consists, as you can see, of a floral spray with ribbon tied in a bow.

In this survey, I have studiously avoided relying on measurements and colors, often useful as a means of identifying the various makers. Unfortunately, it is the sort of piece that admits too much latitude for minute and precise measurements. Suffice to say that the originals are about 7l/2″ long by 53/4″ wide. Identification by color is also unhelpful, as the variety seems infinite and documented evidence is either lacking or imprecise. And as to nomenclature, we need not ask “What Is It?” but do have trouble saying “What’s It For?” Hatch’s original designation as a “fruit dish” has almost been eclipsed by later appellations: a calling-card receiver; pickle, bon bon, candy, nut, mint or berry dish; even a flower float and, thanks to Avon, a soap dish. I have never encountered any reference that dares call it an ash tray. By whatever name, the hands have had a long and fascinating history, admired by collectors and put to many utilitarian uses by those with more pragmatic temperaments. I have often seen them on dealers’ tables and tagged “not for sale”; some dealers use them to hold their business cards, while jewelry merchants find them ideal for displaying their gems and pearls, as if to say, in All State fashion, “You’re in good hands.” 0

Notes:

1 See Rush Pinkston’s review of the article “Imitations of Majolica in Milk Glass” (The Spinning Wheel June 1951) in Opaque News, March 1989, p. 417.

2 S.T. Millard, Opaque Glass (1941), plate 173a, assigns it to Atterbury; E.M. Belknap, Milk Glass (1950), plate 194, notes the existence of modern copies and states it was “originally created by Atterbury.”

3 The Spinning Wheel, Sept. 1960, p. 28. Revi later reported his findings in his book, American Pressed Glass and Figure Bottles (1964), p. 256.

4 U.S. Patent and Trademark Office document.

5 Glass Patents and Patterns (DeBarry, Florida, 1958), p. 12.

6 Shown in Ferson, Yesterday’s Milk Glass Today (1981), plates #182 and #669.

7 Photocopies sent courtesy of P.E. Palao, Museums and Galleries Branch, Office of Arts and Libraries, London, England.

8 See Geoffrey Wills, English and Irish Glass (1968); Collin Lattimore, English 19th-century Pressed-Moulded Glass (1973); Barbara Morris, Victorian Table Glass and Ornaments (1978).

9 Letter to the author, dated 3 October 1991.

10 Letter to the author, dated October 23, 1991.

11 Charles R. Hajdarnach’s recent book, British Glass 1800-1914 (British Museum, 1990) shows the Holyrood hands dish (plate 322) made of clear glass with satin finish in a size I have not encountered. It is smaller (61/8″ in length) and shows some difference in the grapes and leaves design at the wrist, but carries the same English Registry marks as well as the U.S. Patent date. Referencing the book of Barbara Morris, cited above, he also acknowledges the existence of the larger size illustrated in this article.

12 In a little known work, A Guide to Art and Pattern Glass (Pilgrim House Pub. Co., Springfield, Mass., 1960) the author Patrick T. Darr lists a number of modern milk glass reproductions. Of the Hands Dish, he states: “…the finest reproductions made at the present time are from Portugal” (p. 108), but provides no other information to help identify a maker.

13 In the possession of Ruth Grizel and reproduced here with her permission.

14 My dating of Westmoreland’s introduction of its Hands dish was subsequently confirmed by Charles W. Wilson who finds them listed in a WG catalog dated 1940-41. He also informed me that they do not appear in an earlier listing, dated 1932.

15 See Barbara Schaeffer, Glass Review, Sept. 1982, p. 40. The precise date is still debated, but my own research into the matter leads me to agree with Schaeffer.

16 Information sent to the author by John Schnupp, Westmoreland’s production manager, in a letter dated November 14, 1991.

17 Mr. Hajdamach, cited above, mentions his finding unmarked reproductions at antique fairs in 1990, some made in blue, measuring 73/4″ in length, and having a thicker ring-support with ground down rims. Mrs. Frances Price of Bedias, Texas, has a specimen that seems to conform to this description, but neither she nor Mr. Hajdamach are able to identify the maker.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the persons mentioned in the Notes, who have generously assisted me in this research, I wish to thank Duane Sutton (Patent Search Office), Johnny Dingle (Publishing Division), Annie Biondich (Plum Glass Co.), J.T. Yester (Jeanette Shade and Novelty Co.), and Joseph Jankowski (Peltier Glass Co.). And a very special thank you to Frances Price, Faye Crider, Mary Person, Terry Simpson, and Charles W. Wilson for allowing me to examine specimens of the hands dishes in their collections.

Frank Chiarenza, a retired English professor and dean, lives in Connecticut.